By DIANE TENNANT, The Virginia-Pilot © May 26, 2002

Part 1 of 2

SOUTHAMPTON COUNTY — In 1963, the story goes, the last of the Nottoway Indians died.

A fierce tribe of the Iroquois nation had dwindled over 350 years to one old man, illiterate, who worked as a farmhand and rode a bicycle into town for beer.

William Lamb is buried near the farm where he lived and worked, on lands once granted to the Nottoway Indians by the crown of England, to be theirs forever. But the monarch overlooked one thing: The land already belonged to the Indians, had belonged to them for thousands of years, since the ancestors of the clan mothers camped on Stony Creek.

They were Indian lands before John Smith set up fort, before Pocahontas met John Rolfe, before the Tuscarora War and the American Revolution and the Civil War and Virginia’s Racial Integrity Act of 1924.

And one more thing.

William Lamb wasn’t the last of the Nottoway.

The blood that is thicker than Nottoway River water has summoned the descendants. They seek to recover a past that was for so many years denied them.

They call themselves in Iroquois the Cheroenhaka, the People at the Fork of the Stream. They are scattered over at least seven states and Canada. They are coming home, to Southampton County. But like any journey worth taking, it isn’t easy.

Francis Kello stood on the bluff of the old Indian reservation — his family’s land now — looking down at the cypress trees, the elbow of smooth water and the bank where this son of Britain now stores his own canoe.

“You can see why the Indians would pick this site,” Kello said. “It’s the most beautiful high spot on the Nottoway River. I imagine the Indian kids playing up and down the side of these hills like I used to.

“You can go up and down this river, wherever you want, and you won’t find another place like this.”

Which is why the Indians want to come back.

They have been back four, five times since February, when the descendants of the Cheroenhaka (pronounced CHAIR-en-hocka) held their first tribal meeting in Kello’s river cottage. They know they’re Indians, but some are not exactly sure what that means.

When colonial invader John Smith asked the Algonquin around Jamestown what tribe lived to the west, they replied, “Nottoway.” In their language, the term meant “snake” or “enemy.” History, as written by the English, recorded that name.

In today’s Southampton County, the Nottoway River flows, Nottoway House sells furniture and the highway marker beside the high school says “Nottoway Indians.” Some descendants of the tribe who fled north to Canada and Wisconsin, who ended up in Missouri and Ohio and Rhode Island, who live in North Carolina, still use that name.

Those who stayed do not. They want state and federal recognition as the Cheroenhaka. They want their ancestors’ bones back from the Smithsonian Institution. They want to rebury them on Kello’s land.

On Sussex County’s Stony Creek, a tributary of the Nottoway, archaeologists have turned up Indian artifacts from at least 15,000 years ago. These “first Americans” were building fires and making arrowheads 6,000 years before anyone crossed the land bridge between Siberia and Alaska, upsetting theories about the colonization of North America.

These probable Nottoway ancestors moved on downstream, near the present-day county seat of Courtland. While looking for surface arrowheads in the early 1960s, Russell Darden found that looters had been digging for Indian artifacts on the riverbank. A founder of the Nottoway chapter of the Archaeological Society of Virginia, Darden contacted authorities, raised money for a professional excavation and took an active role in examining what came to be called the Hand site.

“We have them dated here in the 1500s,” Darden said. “And that’s pretty definitely a Nottoway village, because of the house construction.”

The archaeologists uncovered the remains of 136 Indians and one white woman, maybe a Spaniard, maybe a Lost Colonist. Most of the Indian bones ended up in the Smithsonian, where they will stay unless the Nottoway can, indeed, gain recognition as a tribe and apply for their ancestors’ repatriation. For now, in the eyes of the government, no descendants remain to claim them.

The English colonists arrived in 1607, but they didn’t meet the Nottoway until 1650, when merchant Edward Bland came upon a village of some 400 people. Their distance from Jamestown — about 40 miles — limited contact with the English.

Still, the Nottoway, along with several other tribes, signed a peace treaty in 1677, which called for a yearly tribute to the governor.

After the Tuscarora of North Carolina lost their war against white settlers in 1713, some of the Nottoway joined their Iroquois cousins in a great migration back to the vicinity of New York.

Those who remained in Virginia were met in 1728 by William Byrd, who found them living around a palisaded fort on what is now Kello’s farm. “The young men had painted themselves in a hideous manner,” Byrd wrote, while “the ladies had arrayed themselves in all their finery. They were wrapped in their red and blue matchcoats, thrown so negligently about them that their mahogany skins appeared in several parts.” Byrd speculated that their dark skin would breed out in two generations.

The Nottoway lived in longhouses, made light-colored clay pottery and weapons of rock that came from as far away as Ohio. Their homeland is now plowed for cotton planting, and Kello’s family collects tobacco pipes and grinding stones after a rain. An avid historian, he is sympathetic to the descendants’ search for their roots.

“I was here one day after it had just been plowed and the sun was just right, and I could see the postholes where the longhouse was,” he said. “I’ve never seen it before, and I’ve never seen it since. But it was beautiful that day.”

The English thought the Indian men should be farmers; the Indians thought farming was woman’s work. They preferred hunting and fishing and, as English settlers closed in around their lands, that became harder to do.

In 1714, Ouracoorass Teerheer of the Nottoway signed another treaty, this one between only one tribe and the crown. The treaty promised the tribe a protected reservation in exchange for a yearly tribute, the learning of Christianity and a warning of any other tribe’s planned attacks on white settlers.

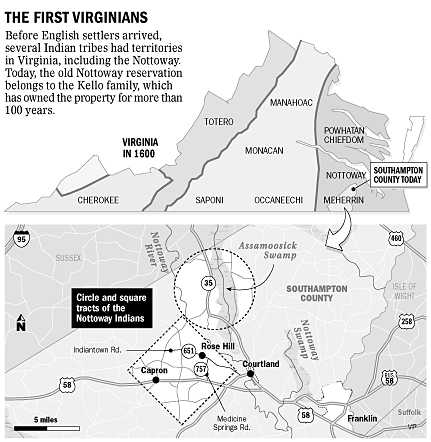

They were given two pieces of land, one described as a circle with a radius of three miles, on the north side of the Nottoway River. The other parcel was a square, six miles on every side, south of the river. Here the Nottoway retreated, and here they found the going rough.

Today, the river water is as much as 20 feet deep in some particularly good fishing spots. The remnants of an Indian fish weir are still there, largely hidden below the surface.

The cypress trees that line the river banks are estimated at 1,000 years old, far older than the reservation. “They grow so slow,” Kello said. “It’s a shame, almost, to cut a cypress tree. You wonder how much longer those old cypress trees will stand.”

Land-hungry Englishmen wondered that about the Nottoway, too.

Unused to farming, trapped by debt and beguiled by alcohol, the Indians began asking the General Assembly for permission to sell or lease parts of the reservation. A 1747 document records the sale of 100 acres for only 30 shillings. It is signed by eight Indians, all of whom used Anglicized names: Winoak Robin, Sam, Doctor Tom, John Turner, Winoak Arthur, Tom Turner, Rodger and Col. Frank.

By 1784, Thomas Jefferson wrote in his “Notes on the State of Virginia”: “Of the Nottoways, not a male is left. A few women constitute the remains of that tribe. They have usually had trustees appointed, whose duty was to watch over their interests, and guard them from insult and injury.”

Around 1792, John Thomas Blow bought the central part of the square reservation. In 1805, his son built Rose Hill, a stately two-story white house that still stands. The property was sold after the Civil War to the Kello family, some member of which has lived there ever since. The Kellos own more than 1,000 acres of former reservation.

“Yeah,” Kello said, “everything around here is Indian.”

The route to Rose Hill goes up Medicine Springs Road to Indiantown Road, which traces the old Indian trail along the edge of Assamoosick Swamp. Kello wore a scrimshaw belt buckle of a three-masted ship under full sail, the kind of ship his ancestors came on in 1741. “You see where that culvert is?” he asked from the front seat of a Jeep Cherokee. “That’s where William Lamb’s house was.”

Up the tractor-rutted road he went, past the white house and the cemeteries for the Blows, the Kellos and the slaves. “Just to the right, in that pine woods, that’s where the old Indian graveyard was,” Kello said. “Sixty-five, 70 years ago, when I used to play through there, you could tell where the graves were.”

Lamb worked for Kello’s mother. Married to a black woman, kin to the Indians, he was buried in a churchyard not far away.

The Kello family has reunions in the small, cinderblock river cottage every year around Easter. Its members come back to the old homestead, look for arrowheads and pottery. Kello has put many of his artifacts in the county museum so no one will forget the Indians.

“I would kind of hate to see them . . .” he paused for reflection. “Well, in one sense of the word, they have disappeared.”

The Nottoway tried, but could not resist, the encroachment of the English and marriage to other races. Unable or unwilling to farm the land, they sold more and more of it. An 1808 census of the tribe named 17 persons.

“Tom Turner, 36 years,” it reads. “He has left his farm in the possession of a mulatto woman who has been kept by him as a wife, the greater part of his time has been generally spent in drunkenness, and the destruction of what little crop he has made; he is the only Indian in his family.

“Littleton Scholar, 51 years. Tillage a small part of his time, balance idle . . . he is the only Indian in his family, his wife being a white woman.”

The bloodlines were starting to separate.

In 1821, some of the more industrious Nottoway made a fateful request to the General Assembly: Divide the reservation, land held in common for the tribe, into individual allotments. The legislators twice rejected the request, but in 1824 they agreed. Some Indians immediately sold their land, others refused even to ask for it until 50 years later.

The Indians who had moved north with their Tuscarora cousins had been assimilated into other tribes, becoming the Sixth Nation of the Iroquois confederation now known as Six Nations of the Grand River reservation near Brantford, Canada.

The Indians in Southampton County were absorbed into the black or white communities. Those who still remembered their Nottoway heritage then encountered Walter Ashby Plecker.

As Virginia’s first registrar of the Bureau of Vital Statistics, Plecker was an outspoken supporter of the Racial Integrity Act of 1924. The act created two racial categories — white and everyone else. Plecker, also a proponent of eugenics, routinely changed the race on birth, death and marriage certificates from “Indian” to “Negro.” Keeping handy a list of Native American surnames, Plecker tried to reclassify every Indian in Virginia, until his retirement in 1946.

Facing segregation and prejudice, Indian descendants began hiding their bloodlines from their children. Calvin Hall of Winton, N.C., chief of the Meherrin Indian tribe, said that when he was 8 years old, in the 1940s, he ran home from school to tell his grandmother about his lesson on Pilgrims and Indians. “She said, `We’re all Indians, but we can’t talk about it.’ We didn’t talk about it.”

The act was struck down in 1967 by the U.S. Supreme Court, but the damage was done: Generations had grown up believing they were either black or white, and official documents confirmed that.

Those who held on to their Indian identity paid a different price. Norbert Johnson’s father was placed in an orphanage in the 1930s because his mother was teaching him drumming and dancing. “The community thought it was an uprising or something,” Johnson said from his St. Louis home. “There were a lot of people placed in orphanages or sent to different Christian homes. It was to eliminate the savage in them.”

Johnson grew up to join the military, begin genealogical research and now, after retirement, to spend 80 percent of his time working on Native American issues, including the return and recognition of the Nottoway.

“A lot of people think this is really cool,” he said. “But a number of years ago, when it wasn’t fashionable to be Native American, I was Native American.”

Johnson is helping the Nottoway Confederation, a loose affiliation of descendants in North Carolina, Wisconsin, Ohio and other states, seek a legal clarification from Virginia’s attorney general on the tribe’s status.

“The No. 1 thing to do is restore the Nottoway in Virginia,” Johnson said. “The Nottoway who are there, the ones who stayed behind, have a right for the reclamation of their heritage. The people are being called for some reason to call each other, without knowing our history, our genetic ties. If you understand anything within the spiritual world, it’s a gathering. We’ve most definitely changed our shapes, but there’s a desire to return.”

Johnson spoke of buying back tribal lands, of setting up health clinics for Native Americans, of returning the Nottoway culture to Southampton County.

To gain state and federal recognition as the Cheroenhaka/Nottoway, the descendants in Virginia will have to document Indian blood, a task complicated by Plecker’s erasure of their past. They must search for key surnames, notations of “colored,” “mulatto” or even “Portugee (Portuguese)” in birth certificates, marriage licenses, deeds, jail records, wills and other documents.

“We’re descendants,” Johnson said. “We all have a right to reclaim that that was once part of our history.

“Some were classified as white or black. Those who remained behind were called colored. That creates the issue of who are they?

“Legally, morally, culturally, who are they?”

Reach Diane Tennant at 446-2478 or dianet@pilotonline.com